On the Genealogy of a Bad Sauna - Part III

The Age of the Machine

Steam bath devices of the 1800s

This is the third part of a five-part exploration of sauna pods, optimization culture, and the joys of bathing.

“The tool changes nature and man at the same time: it subjugates nature to man, who makes and uses it, but it ties man to subjugated nature.”

—Georges Bataille, Theory of Religion, p. 41

By the 19th century, the machine had become the central metaphor for the human body. Gone was any notion of the body as a source of powers, desires, needs, or mysteries—or as a vessel for spirit. What remained was merely a machine to be geared and fine-tuned, a product to be manufactured. The primary social relationship thus became one of self-ownership, self-management, and self-improvement. This period saw the invention of devices fashioned to “scientifically” enhance the body’s functioning, including “powering” the body with electricity and radium “therapies.” By the late 19th century, the emergence of scientific management theory further reduced human labor to mere cogs in a machine by engineering their every movement in the production process.

The personal steam cubicle, with its focus as a treatment for physical ailments ranging from gout to pulmonary diseases, found a receptive audience in this machine-focused society, especially as it came more and more to resemble an appliance.

American Steam-Bed Bath, 1814 (U.S. Patent 2049x, 21 January 1814)

German steam bath device, 1827.

Steam-Bath Apparatus, 1855 (U.S. Patent 13,467, 21 August 1855)

Bath Cabinet 1897

This period also saw the introduction of traditional European sweat bathing practices to the American landscape—including the Finnish sauna, the Jewish schvitz, and the Turkish hammam—but these never caught on with the mainstream public in the way that the personal sweat cubicle did. A survey of ads from this period suggests an explanation for the popularity of sweat cubicles, which often claimed superiority to Russian and “Oriental” baths in terms of their portability, convenience, and economy of time. Apparently, little regard was given to other, non-productive features of the Russian banya or the Turkish hammam, such as their communal nature, comfort, or quality of sensation.

The Barberg–Selvälä–Salmonson Sauna, a traditional Finnish savusauna (or “smoke” sauna) in Cokato Township, Minnesota. Built in 1868, it is believed to be the oldest surviving smoke sauna in the United States.

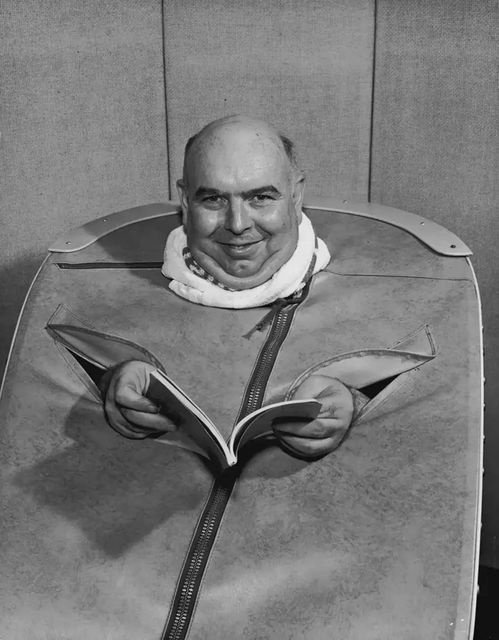

Personal sweat appliance of the 1950s

Sweat pod, 1971

Common sauna pod on amazon.com, 2025

In the 20th century, the sweat cubicle continued to be marketed along medical lines. However, it increasingly became associated with more aesthetic concerns such as weight loss and beauty. This gradual move from functionalism to aesthetics mirrored a changing economy that had transitioned from meeting needs to creating desires.

It was during this period that the Hydro-Massage Company in Chicago, Illinois, produced the mustard yellow sauna pod I discovered on Facebook Marketplace, some seventy years later.

Something about this strange device caught my attention. It was ugly and obsolete, yet oddly appealing—a relic of productivity now rendered utterly frivolous by the passage of time. On a lark, I took a ride across the state line to Middlefield, Ohio and met a guy at his storage unit located behind a Dollar General. So close was the association between sauna and weight loss that when I handed him the money, the seller made a comment about how much weight I was going to lose.

This is the third part of a five-part exploration of sauna pods, optimization culture, and the joys of bathing. Stay tuned for the fourth and final part, on the Good, the Bad, and the Optimum sauna.